Headline: Apple Watch Pre-Orders Shipping Earlier Than Expected. Translation: Apple BTO production ramping up nicely w/o glitches so far.

Daily Archives: April 22, 2015

Oracle CEO Mark Hurd: ““Big Data, in my opinion, i…

Status

Oracle CEO Mark Hurd: ““Big Data, in my opinion, is just lots of data.” Gosh I had no idea….

bizjournals.com/boston/blog/bo…

2010 Crash comment: “Since most of the people in s…

Status

2010 Crash comment: “Since most of the people in stock markets these days are robots, relying on them to act like robots can actually work”

According to Google, I am a giant squid. That is a…

Status

According to Google, I am a giant squid. That is all.

Here’s my detailed followup to last week’s Apple W…

Status

Here’s my detailed followup to last week’s Apple Watch post: Why Watch Margins Should Set A New Record for Apple. carlhowe.com/blog/why-watch…

Why Watch Margins Should Set A New Record For Apple

Quote

Quick look

The bottom line for those who don’t want to read further: the blended gross margins for all versions of Apple Watches should approach 75 percent, making the Apple Watch the most profitable of all Apple products.

According to my revised Apple Watch launch model, it costs less than $150 in parts and labor to build an Apple Watch without the case and band. Include the case and band, and the total cost and labor for the Apple Watch Sport is still only $152. That means that if the average selling price for an Apple Watch Sport is $379, that product will yield a 60 percent gross margin. That margin picture becomes even rosier as we move up the Apple Watch ladder: I see Apple watches yielding 77 percent gross margins, and Edition Watches generating a whopping 86 percent margin, even including the cost of the gold used. Combining all of these along with the estimated 59/40/1 percent split among Sport, Watch, and Edition models, and I expect to see a blended gross margin from Apple Watch to be around 75 percent.

How can Apple command these prices when more complex devices such as PCs command gross margins in the single digits? The answer is surprisingly simple. People buy PCs for what they do; people buy watches for how they look. Apple can command record margins for its Watch products for the same reason that Vermeer paintings created with cheap oil paint on canvas sell for millions of dollars: people will happily pay for beauty.

Defining Gross Margin

In big data science, my current occupation at Think Big Analytics, the biggest insights often come from joining information from multiple datasets to reach new conclusions. That’s what I’m going to do in today’s post about the Apple Watch, many of which are currently winging their ways to consumer doorsteps.

The specific metric I will estimate is one that is a bit financially geeky: gross margin. For anyone who isn’t familiar with the term, Wikipedia defines it as follows:

“Gross margin is the difference between revenue and cost before accounting for certain other costs. Generally, it is calculated as the selling price of an item, less the cost of goods sold (production or acquisition costs, essentially).”

Gross Margin is not the same as net profits or net margins. Net profits get calculated by subtracting other costs such as marketing and overhead from the gross margin figures. However gross margin is usually used as a way to compare different products for how much value they add to a business. A product with high gross margins is considered better than one with low gross margin if product volumes are equal.

Today’s Thought Experiment

Last week, I asked readers to imagine how they’d manufacture a million Origami lobsters out of paper. I’m going to continue that though experiment theme this week with a different question. If you’re not interested in such context, skip ahead to the next section where we’ll dive into revisions to the model I posted last week.

Meanwhile, this week’s thought experiment question is this:

What were the parts cost and gross margin of a Johannes Vermeer painting in his day?

Johannes Vermeer, of course, was a modestly successful 17th century Dutch painter, known for such paintings as Girl with a Pearl Earring and The Music Lesson. Art historians the world over praise his works for their subtle portrayal of light and his use of brilliant and lifelike color. Today, historians attribute 34 surviving paintings to undoubtedly be Vermeer’s work. While priceless due to their rarity, owners who have sold Vermeer paintings have invariably seen prices in the tens of millions of dollars.

But what did they cost to paint?

I’m no art historian, but I can make some guesses based using information from The Essential Vermeer, a web resource about the painter curated by American painter and historian Jonathan Janson. Using some of the articles there, we can compile a rough cost estimate for a painting by our friend Vermeer done over a few months pretty easily:

- Canvas and frame. Canvases were cheap, but we’ll use 1 guilder as an estimate and use the same for the frame. Just as a benchmark, an average cloth-worker in Delft was paid about one guilder a day.

- Paints. Vermeer is famous for using expensive paints such as lapis lazuli, natural aquamarine, and Indian yellow. Expensive in this case is relative term; we’ll give him 7 guilders for his expensive paints.

- Brushes and other tools. These were largely tools of the trade amortized over many paintings. Chalk up another guilder for tools.

- Labor. This is perhaps the most difficult component to estimate, although interestingly, some painters of this period did insist on being paid for their work by the hour. Most would subsist on sales of paintings and income from teaching apprentices, who could handle much of the routine work in putting together a painting. Because a painter might work on multiple paintings at once and could offload tedious work onto apprentices, I’m just going to guess that the labor involved was the largest component and was about 50 guilders.

That gives us a total parts cost for a Vermeer of about 60 guilders. Now what would such a painting sell for in that day?

Again, here I’m going to look to others for the estimate, but a Rembrandt portrait in that day would sell for about 500 guilders and a small genre piece by Dou (another famous artist there) could fetch up to 1,000 guilders. Hendrick van Buyten, an owner of at least three Vermeer paintings during this period, shocked a visiting French aristocrat by saying that he had paid 600 guilders for one of Vermeer’s paintings. That suggests that Vermeer painting had something on the order of 90 percent gross margins.

To anyone in the art business, applying a metric like gross margin to an artist like Vermeer is hear heresy; we view Vermeer as an unparalleled artist for whom business metrics don’t really apply. However, in his day, Vermeer had to make a living as a painter. While he may not have explicitly targeted 90 percent gross margins, I’m sure that the fact that he sell his paintings for more than it cost him to make them certainly helped him survive in the competitive Delft art business where other masters such as Rembrandt lived.

Just to finish up this thought experiment, how did Vermeer’s gross margins compare with others in the same town and school of painting?

As we might expect, Vermeer was exceptional. As the source I noted above says, 20 guilders was a good price for a painting. That low generic price raises another yet another question: what made Vermeer’s paintings fetch prices that were 30 times higher?

The answer, of course, is beauty. Vermeer’s paintings were extraordinarily beautiful, even compared to others of the Delft guild. Vermeer’s artistry was so profound that his works became iconic and recognizable at a glance. The value of a Vermeer painting in the 1600s and today has nearly nothing to do with its parts cost and gross margins. A Vermeer’s beauty and craftsmanship defines its value, not its parts cost.

Keep that in mind as we now return to my claim that the Apple Watch will fetch record high gross margins.

My Watch launch model origin revisited

Last week I wrote about a very simple-minded model that predicted initial Apple Watch sales to be more than 3 million units for revenue of $2.2 billion by May 8, 2015. This week, I’m examining what Apple expects to see from its Watch investments, namely, record high gross margins.

Since last week, I’ve had some feedback from readers about my model, and I’ve made some changes in response. In particular, John Gruber of Daring Fireball commented:

“I think he’s made some smart guesses as to the product mix between Sport/Watch/Edition, but if I had to adjust his numbers at all, I’d move the number of Edition models Apple will sell slightly up. In Howe’s estimate, Sport is outselling Edition by about 45-to-1. But if it’s more like 30-to-1, the Edition line would account for as much or more total revenue, and certainly more profit. I’m guessing at an average selling price of around $400 for Sport (more 42 mm than 38 mm, plus lots of extra bands). But let’s say it’s as high as $425. At that ASP, 30 unit sales equals $12,750 in revenue. Given the prices of the Edition line (42 mm with Sport band costs $12,000; the ones with leather straps are $15-17,000), I’d imagine the ASP for Edition will be at least $12,750.”

As such I’ve refined and revised my average selling price’s (ASPs) for the model by:

- Boosting Sport ASP slightly to $379. While I accept John’s argument that consumers prefer the 42mm units, I’m not including extra band revenue in my model presently. If we assume a 60:40 split on the watch sizes, with 60 percent of orders favoring the 42mm model, that leaves us with a Sport ASP of $379 instead of the $375 I estimated before.

- Decreasing Watch ASPs slightly. With 20 different combinations of colors, bands, and prices in the Watch collection, not all of which are orthogonal, I think it’s overkill to estimate each model’s sales for a more precise ASP. Therefore, I’m simply going to average the prices of all band types for each size and add those averages together weighted by the 60:40 size preference. That results in a blended ASP of $745, which is a bit lower from my prior estimate of $760.

- Increasing Edition ASP to $14,200 and volume to 60,000 units at launch. As one commenter pointed out, I don’t think most people spending $10,000 to $12,000 on a gold watch are going to buy it with a $49 plastic band. As such, I’m modeling a 3:1 preference for the more expensive bands for the Edition collection as well as the 60:40 preference for larger watches. That creates an ASP of $14,950 for the Edition collection which feels closer than my prior estimate of $12,500

I should note that I’m using US dollar prices here. With Apple Watch launching in 8 countries other than the US, we may see higher actual ASPs simply due to higher equivalent US dollar pricing in other countries. For now, though, I’m going to ignore that effect entirely as being out of scope.

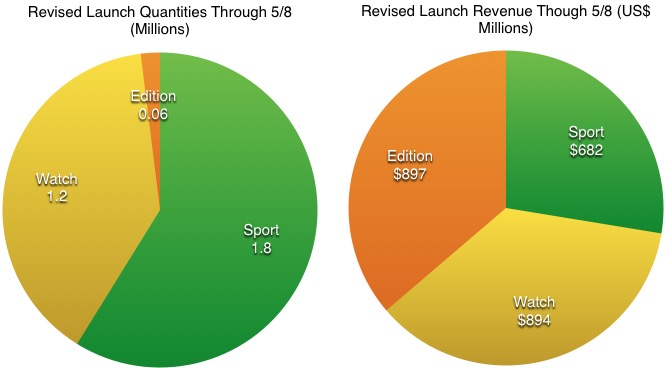

Clearly this changes the launch picture quite a bit, so here are the graphs what I think launch shipments and revenue will look like now:

Figure 1: Revised Apple Watch Launch volumes and Revenue As Of April 22, 2015

What’s interesting about this result is the roughly equal contribution of revenue among the three collections and the inverse relationship between shipment volumes and revenues. The Sport watch dominates launch “market share” with 1.8 million units, but is in last place in revenue with $682 million because of its low ASP. The Edition collection ships a mere 60,000 units, but its nearly $14,000 ASP drives the Edition revenue to $897 million, which is $3 million more than The Apple Watch. If you accept this model, then Apple has crafted three near-equal revenue streams within the Watch family that appeal to three very different buyer profiles and volumes.

The cost of Watch parts

With the model revisions out of the way, we can now turn our attention to margins. For this model, I’ve used an iPhone 6 teardown cost model published by Techinsights at teardown.com. You can see the original model here.

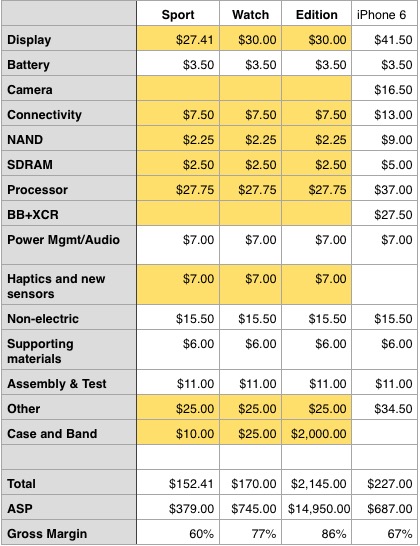

My new model can be seen in Figure 2 below:

Figure 2: By Using Common Parts Among Different Watch Collections, Apple Watch Achieves Record Gross Margins

I’ve highlighted in yellow the parts that I’ve changed for each model of watch. I’ve changed the Techinsights iPhone 6 model by:

- Lowering the display cost. NPD DisplaySearch has estimated that the cost of the display for the Apple Watch is $27.41. I’ve boosted that to $30 for Watch and Edition collections to account for the addition of sapphire crown on top of the display, but all values are less than the iPhone 6’s $41.50.

- Eliminated the camera and broadband components. Apple Watch has no camera, so we can eliminate that cost.

- Significantly lowered radio costs. iPhone 6 has cellular radios covering 2G, 3G, and LTE on multiple bands. Given that Watch has no cellular connectivity, we can eliminate all broadband and XCR costs. I’ve also cut Bluetooth and WiFi LAN connectivity costs as well because the use cases aren’t as demanding and the function be done pretty much all in one component.

- Lowered processors costs. The processor powering the Apple Watch’s S1 is less complex than the A8 in the iPhone 6, so I lowered its cost by $10.

- Reduced other costs because of less complexity. While Watch is a complex device, it’s complexity is nowhere near that of the iPhone 6. With fewer parts involved other than those explicitly called out, other costs should be lower too.

While those factors reduce the parts cost, I added some new costs as well for

- The haptic system. I estimated this figure to be about $7 in parts per device, using the power management and audio cost as my proxy.

- Cases and bands. This is the area of greatest difference among the Watch collections. I’ve estimated the aluminum case and sport band to cost roughly $10 in materials cost, the stainless steel cases and bands to average $25, and the Edition cases and bands to cost around $2,000.

When we compute the results from making these adjustments, we see that Apple Watch Sport should earn a roughly 60 percent gross margin, Apple Watch will earn about 77 percent, and Apple Edition will achieve 86 percent gross margin. The latter two figures both substantially exceed the gross margins achieved by the iPhone 6 and I believe will represent new high-water marks across all Apple product lines.

The source of Watch value

As I noted in my first post, Apple has designed the three models of Apple watch to all use common electronics, displays, and parts, with exceptions only for cases, bands, and display crowns (the Apple Watch and Edition use single crystal sapphire display crowns, while Apple Watch Sport uses Ion-X glass). This design of one electronics assembly powering three products set at three significantly different price points that differ only by case materials and a few mechanical parts creates a product family that can earn very high margins. Add in Apple’s brand, retail reach, and ability to charge premium prices, and you have a product line poised to become a multi-billion dollar business with record profits the first two weeks it is on the market.

Said another way, smart design, reusable parts, and pricing power create high margins. That, at least, is the MBA version of the story.

Frankly, if that were true, I think we’d have a lot more fine Apple Watch competitors being made by other companies. After all, they have smart MBAs too.

Instead, what I think has happened is Apple Watch product family has been designed to help Apple enter a new higher margin business. First, Apple was a computer company. Then it became a mobile device manufacturer with the iPod and iPhone. Now with Watch, Apple is becoming a maker of functional jewelry.

Apple designer Jonny Ive has said that the Apple Watch is “the most personal product Apple has ever made” and used that statement as justification for the myriad case and band designs offered with Apple Watch. But I think the Watch has a unique characteristic that has been overlooked by most observers: Apple Watch is only the second Apple product where the user spends most of his or her time in contact the device without its display being active (the first was iPod). Further, almost everyone who sees someone else with an Apple Watch will almost never see its display. As such, the design of the non-electronic parts of the Watch—the case, the bands, the buckles—now become a much larger part of the device’s value. Apple is now in the jewelry business, and in jewelry, design and beauty matter.

Now we expect value to come from artistry and craftsmanship when we buy jewelry. You can buy a platinum 2-caret solitaire diamond ring off the Internet for about $11,000, and you can buy a very similar platinum 2-caret diamond ring from Tiffany for about $40,000. Design, quality of materials, artistry brand, and warranty all factor into the final price, but at the end of the day, the price comes down to how much the buyer is willing to pay for beauty, knowing that the ring will be worn for years if not decades to come.

By combining all those factors into its signature jewelry products, Tiffany commands 64 percent gross margins over all its product lines. Apple, meanwhile, averaged 40 percent across its businesses in the quarter ending December 31, 2014. The tens of millions of dollars Apple is spending on sold gold cases, private showing rooms, and intricately engineered link bands for its Watches are Apple’s investment to do business with jewelry margins instead of technology ones. Assuming that my models aren’t completely off-base, it looks to me like those investments will pay off handsomely.

I started this piece with a thought experiment about Vermeer, and, despite my affection for Apple products, I do not claim that Apple Watches are ever going to be as valuable as Vermeer paintings. However, Vermeer himself never imagined that a Vermeer painting in his day would be worth tens of millions of guilders either; he was happy to sell them for a few hundred guilders because those sales allowed him to continue his pursuit of art through his painting.

I believe that Apple has entered an era where creating beauty now adds as much value as its technology does. Those skills aren’t going to show up on a balance sheet or in a parts cost analysis, but increasingly they will define who and what Apple will be in the future.

This skeptical article about Tesla today http://t….

Status

This skeptical article about Tesla today fool.com/investing/gene… is fun to compare with this one about Apple in 2009. bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=…

Auto-play videos are a plague on the Internet. Fir…

Status

Auto-play videos are a plague on the Internet. First CNN, now Bloomberg. Don’t waste my bandwidth people—I actually read my news.

The birds at our feeder get bigger every year. htt…

Status

The birds at our feeder get bigger every year. http://t.co/VzJIiG1ggs