The media has written many dramatic accounts of the May 7 accident involving a Tesla’s collision with a tractor trailer. Some read as if Elon Musk, Tesla and autopilot technology caused the death of the driver. As someone who has both flown as a pilot using autopilots and as the owner of a Tesla with autopilot functions, I don’t think this is accurate. I’m hoping that this response will provide some balance in the discussion.

Based on my experience with Teslas, aircraft, and technology analysis in general, I assert the following:

- The accident was caused by driver negligence, pure and simple

- Even including this fatality, data on autopilot use indicates it is safer than manual driving.

- Legal precedents already exist for how autopilots can and should be used

- The issues regarding autonomous self-driving cars (as opposed to autopilots) will take at least a decade to be resolved.

With that as preface, let’s take the arguments one by one.

1. The accident was caused by driver negligence, pure and simple.

First, autopilots (the technology the Tesla was equipped with) and autonomous self-driving vehicles (think of those Google self-driving cars) are not the same thing. The U.S. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) defines four levels of vehicle automation, each with differing requirements. The Model S Tesla autopilot involved in the accident was a Level 2 system, which the NHTSA defines as:

[A level 2 system] involves automation of at least two primary control functions designed to work in unison to relieve the driver of control of those functions. An example of combined functions enabling a Level 2 system is adaptive cruise control in combination with lane centering.

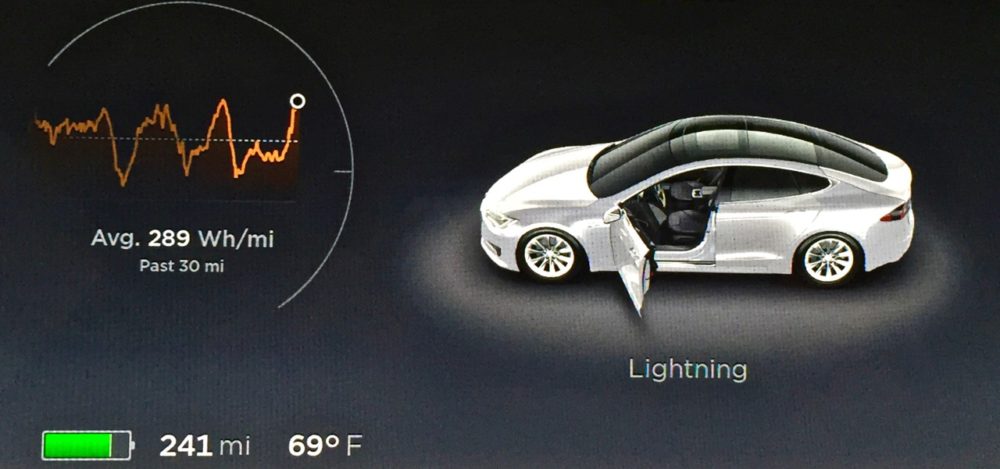

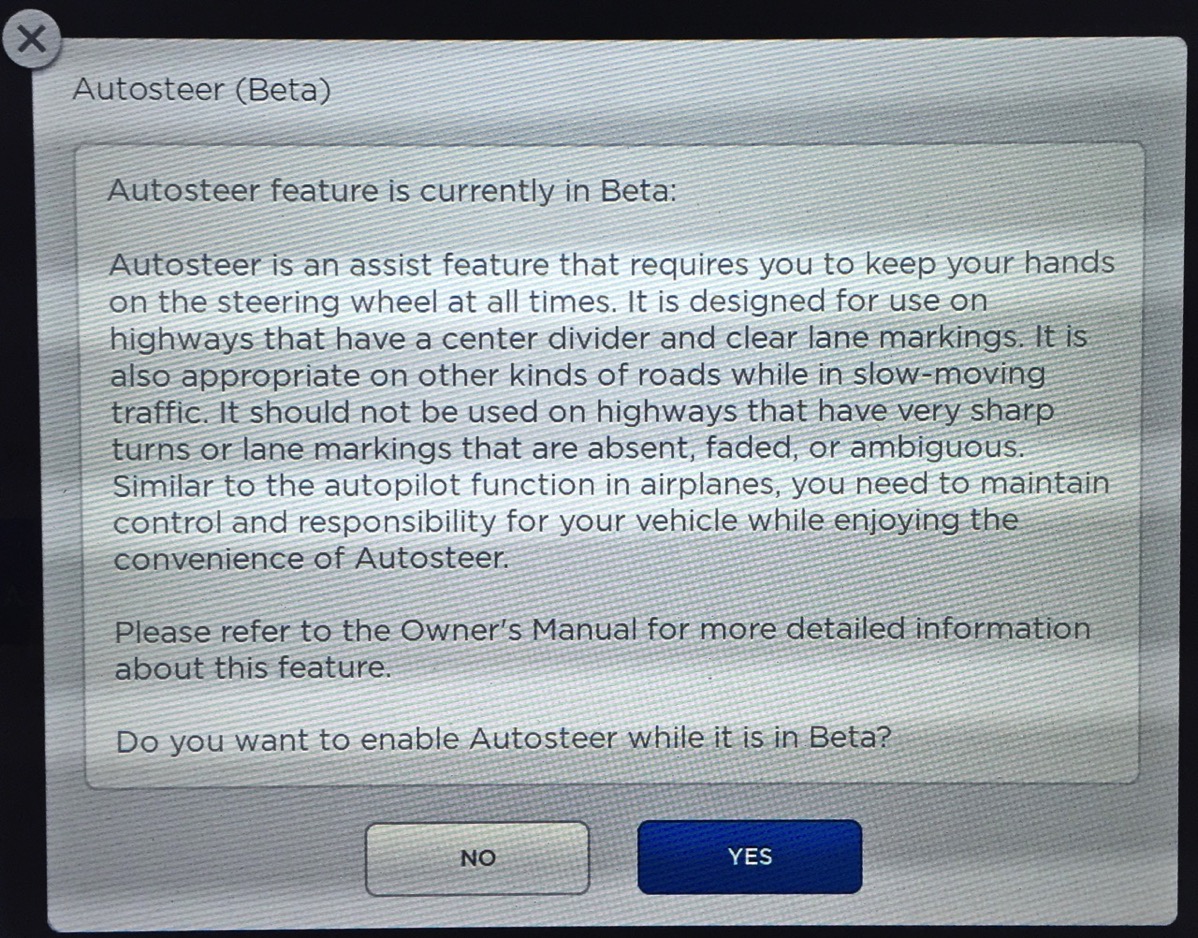

The driver was notified of the limitations of the Tesla autopilot when he first accepted the risks of using the beta autopilot. as shown in the screen shot at the top of this article. Further, every time he invoked the auto-steering function on his car, he was again reminded by a notice on the dashboard that he was to keep his hands on the wheel, retain control of the car, and to be prepared to take over at any time. The fact that the driver then saw fit to watch a movie instead of the road was just as negligent in an autopilot-powered car as it would have been on one where there was no autopilot. He did not avoid an obstacle when driving his car, and that caused an accident. If the driver had lived, it seems likely that he would have been found negligent in a court of law simply because the law requires drivers to be in control of their vehicles at all times, regardless of what bells and whistles they may have bought.

Bottom line: the driver was negligent, not the autopilot.

All the arguments you hear about autonomous self-driving cars are about level 4 systems, which we’ll define and discuss in the fourth section.

2. Even including this fatality, what data we have on autopilot use indicates it is safer than manual driving

As the Tesla team notes in their blog, the average fatality rate for US drivers is approximately one fatality every 94 million miles. The latest data for 2015 from the NHTSA shows that U.S. fatalities actually increased in 2015 to one fatality every 89 million miles.

Despite the Tesla driver’s poor judgment, the accident reported in May is the first fatality reported in 130 million miles of autopilot-enabled driving; in fact, it is one of only a very few fatalities ever to occur in a Tesla. Just based on these statistics, fatalities in a Tesla on autopilot occur at 68% of the rate in ordinary, non-autopilot-equipped cars.

3. Legal precedents already exist for how autopilots can and should be used

The first autopilot on an aircraft was demonstrated by Lawrence Sperry in 1914 on the banks of the Seine in 1914. Seemingly foreshadowing this recent Tesla incident, Sperry left the cockpit and allowed the aircraft to fly itself past the grandstands with no pilot at the controls in what was probably the first example of irresponsible use of an autopilot.

Since that time, literally billions of passenger miles have been flown under autopilot control. A 777 today can fly itself from a runway at New York’s JFK and land itself at a category IIIc runway at London Heathrow without the pilot ever being involved or the passengers ever knowing. Today’s autopilots are so good that pilots often have to take extraordinary measures to avoid falling asleep in the cockpit. Suffice it to say that aircraft autopilots are decades ahead of autopilots in automobiles, and they use equipment that is orders of magnitude more precise and costly.

Despite the capabilities of today’s aircraft autopilots, though, aviation law is quite clear: aircraft must have a pilot in command, and that pilot is ultimately and legally responsible for the operation of the aircraft. It is his or her responsibility to decide when to use the autopilot and whether it is safe to do so. The pilot in command is also responsible for understanding the limitations and possible failures of autopilot hardware and to be prepared to override the autopilot at any time.

In short, the legal buck always stops with the pilot, not the aircraft or the autopilot manufacturer, regardless of how good or bad those products may be. If that’s the case for autopilots that costs hundreds of thousands of dollars, it seems unlikely that we would absolve drivers of all driving liability when they rely on new systems that cost a few thousand.

4. The issues regarding autonomous self-driving cars (as opposed to autopilots) will take at least a decade to be resolved.

As noted in my first argument, despite being the most advanced car autopilot made today, Tesla’s autopilot is a level 2 system that is only designed to relieve the driver of some tedious tasks; it is not a fully autonomous level 4 self-driving system such as those being tested by Google and Audi. The NHTSA defines a level 4 autonomous system as:

[In a level 4 system,] The vehicle is designed to perform all safety-critical driving functions and monitor roadway conditions for an entire trip. Such a design anticipates that the driver will provide destination or navigation input, but is not expected to be available for control at any time during the trip. This includes both occupied and unoccupied vehicles.

Startups, automakers, venture capitalists, and the media have been breathless in their excitement about autonomous vehicles. Many seem to hoping for a world where they can get smashed at parties, summon their vehicles to take them home, and to be comforted by the knowledge that technology will get them home safely. It’s the ultimate Silicon Valley dream and promises to be worth billions.

I assert that the dream of level 4 autonomous vehicles will likely turn into an ethical and legal nightmare. The problem is not one of technology, but of philosophy and ethics. A self-driving car sounds innocuous, but in reality, is a software-controlled two-ton object that can’t overcome the laws of physics. A two-ton vehicle traveling at highway speeds has plenty of momentum to kill.

That claim may be hyperbolic, but consider the following scenario: An autonomous vehicle carrying two passengers is traveling the speed limit on a two-lane road with a car coming from the other direction. A child dashes out from behind a tree in front of the autonomous vehicle so close that it cannot stop. If the car swerves to the right, it will likely hit the tree and kill the occupants. If the car swerves to the left, it will have a head-on collision with the oncoming car and will likely kill the occupants. Even if it brakes perfectly, it will still kill the child. What is the correct course of action for the car, who is responsible for the inevitable deaths, and, more importantly, will any of those actions be acceptable to society?

If you find this scenario too outlandish, how about this simpler all-too-familiar one to the tech world: A consumer tasks an autonomous vehicle to take him or her to work on the 70 mph freeway. Enroute, the autonomous software stops responding, and the car plows into several others, creating a multi-car accident. Who is responsible and pays for the damages: the consumer, the auto manufacturer, the autopilot programmer, or all of the above?

Finally, let’s consider a more nefarious use of automobile autonomy: a terrorist loads up an autonomous vehicle with explosives, sets its destination for some government building, and then gets out of the car. Will society accept this scenario as an acceptable risk of self-driving vehicles?

I believe that the legal system and our courts will eventually sort out the grim implications of fully autonomous vehicles, but I don’t think this will happen quickly or easily. Further, with billions of dollars in R&D and product liability at stake, many of these issues will need to be resolved either legislatively or by the Supreme Court before they are settled law. Perhaps the industry will ultimately come up with the equivalent of Isaac Azimov’s Three Laws of Robotics to govern autonomous vehicles; after all, an autonomous vehicle is simply a robot in the shape of a car. Regardless, I predict that it will be at least one decade and probably several before the law and society come to grips with these issues in any understandable and enforceable way.

In the meantime, though, autopilots such as Tesla’s will show up in more vehicles over time. In the absence of settled law, motor vehicle regulators and insurers are most likely to fall back on the only precedent they have: the driver is ultimately responsible for safely operating the car and autopilot, just as pilots are in aircraft.

Yes, we will see more fatalities when people use those tools irresponsibly. And while we may aspire to create autonomous technology that is near-foolproof, mother nature will always create better fools.